So, in year 20, I will continue to do what I have always done and do my best to represent people accused of crimes in Grayson, Fannin and sometimes Cooke County. I had the opportunity to run for district attorney in one of our counties but could not bring myself to do so. I love helping people accused or investigated for crimes get to the best result possible, especially when that result is a changed life. Due to my family dynamics and education, I have more insight than most in my opinion to mental health and substance abuse issues, which is an overwhelming need in the criminal justice system. Even in a wrongful arrest case, I tell people to let the situation be a reason they change their life for the better. God never puts us through anything that isn’t designed to improve us instead of break us.

So, in year 20, I will continue to do what I have always done and do my best to represent people accused of crimes in Grayson, Fannin and sometimes Cooke County. I had the opportunity to run for district attorney in one of our counties but could not bring myself to do so. I love helping people accused or investigated for crimes get to the best result possible, especially when that result is a changed life. Due to my family dynamics and education, I have more insight than most in my opinion to mental health and substance abuse issues, which is an overwhelming need in the criminal justice system. Even in a wrongful arrest case, I tell people to let the situation be a reason they change their life for the better. God never puts us through anything that isn’t designed to improve us instead of break us.

So, I will continue to stay here at 711 N. Travis in Sherman, Texas, where my friend Jack McGowen always officed and taught me so much. Joey Fritts, my friend and companion in criminal defense for many years, is no long with us along with others that I have learned a lot from along the way. Don Bailey is still in the barn down the street on Willow where I learned so much federal law, and John Hunter Smith is in the Castle on Washington Street where he taught me a ton, along with at the courthouse, and where I used to go see Christmas lights as a young kid. Sherman is home and will always be home for my practice.

Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

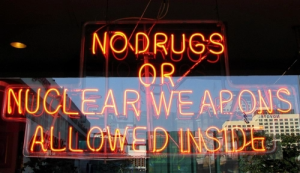

I eventually got really tired of the relapse levels of some of my clients and the reality of substance abuse and mental health populations in general, and starting using licensed chemical dependency counselors about seven years ago to help lower the recidivism rate and get people into treatment up front for better results and a changed life. I have always told clients to do what is in their long-term best interest, not just their short-term best interest. It is our job to do the math for them both short term and long term, and when a client is addicted to hard drugs such as methamphetamine, opiates or alcohol it can be a tough habit to break. We have really good treatment programs in Abilene at Concho Valley and the Bowie Women’s program, and some midlevel like SAFP that can make a big difference if a person self-invests. As the majority of substance abuse clients are self-medicating for undiagnosed or untreated mental illness, or some trauma, it’s very important to get the right counselor in there to help them understand not only their addiction but their triggers. I find it very rewarding when we can help people turn their lives around and see them at the grocery store or somewhere else in public a few years later a changed person. Addictions can be overcome, whether its substance abuse or other behaviors, but the work has to be put in.

I eventually got really tired of the relapse levels of some of my clients and the reality of substance abuse and mental health populations in general, and starting using licensed chemical dependency counselors about seven years ago to help lower the recidivism rate and get people into treatment up front for better results and a changed life. I have always told clients to do what is in their long-term best interest, not just their short-term best interest. It is our job to do the math for them both short term and long term, and when a client is addicted to hard drugs such as methamphetamine, opiates or alcohol it can be a tough habit to break. We have really good treatment programs in Abilene at Concho Valley and the Bowie Women’s program, and some midlevel like SAFP that can make a big difference if a person self-invests. As the majority of substance abuse clients are self-medicating for undiagnosed or untreated mental illness, or some trauma, it’s very important to get the right counselor in there to help them understand not only their addiction but their triggers. I find it very rewarding when we can help people turn their lives around and see them at the grocery store or somewhere else in public a few years later a changed person. Addictions can be overcome, whether its substance abuse or other behaviors, but the work has to be put in. I also started doing Federal CJA appointments in 2006 and it took about five years to really begin to learn what I was doing in federal court, which is normal for most lawyers. The Sentence Guidelines are a penal-mathematical formula that every attorney must try to master and none completely do so due to the level of discretion, change and ambiguity involved. But, one learns early on that the name of the game more often than not in Federal court is cooperating with the federal government and your guidelines and treatment are usually better. There is even a third or half-off sentence reduction for substantially assisting the federal government in prosecuting other people. Especially in the Eastern District of Texas, things normally tend to get worse with a jury trial in Federal Court unless you have a really good case for a not guilty verdict. Some do, and we do see not guilty verdicts and dismissals.

I also started doing Federal CJA appointments in 2006 and it took about five years to really begin to learn what I was doing in federal court, which is normal for most lawyers. The Sentence Guidelines are a penal-mathematical formula that every attorney must try to master and none completely do so due to the level of discretion, change and ambiguity involved. But, one learns early on that the name of the game more often than not in Federal court is cooperating with the federal government and your guidelines and treatment are usually better. There is even a third or half-off sentence reduction for substantially assisting the federal government in prosecuting other people. Especially in the Eastern District of Texas, things normally tend to get worse with a jury trial in Federal Court unless you have a really good case for a not guilty verdict. Some do, and we do see not guilty verdicts and dismissals. It is always a challenge to get juries to understand what the problems were on a machine that the state put forth as scientifically qualified. The State of Texas was the last one to finally upgrade to the Intoxilyzer 9000, which still has some issues. But back then, most of the trials were chemical test refusals and we normally fought over how intoxicated a person looked on video. Now, the arresting officer almost always gets a search warrant if someone refuses to consent to a blood draw. The State tries to do all they can to make license suspension hearings and DWI trials more winnable for them, but there are still errors and ways to win. I won a blood test above .2 in Fannin County a couple years ago now.

It is always a challenge to get juries to understand what the problems were on a machine that the state put forth as scientifically qualified. The State of Texas was the last one to finally upgrade to the Intoxilyzer 9000, which still has some issues. But back then, most of the trials were chemical test refusals and we normally fought over how intoxicated a person looked on video. Now, the arresting officer almost always gets a search warrant if someone refuses to consent to a blood draw. The State tries to do all they can to make license suspension hearings and DWI trials more winnable for them, but there are still errors and ways to win. I won a blood test above .2 in Fannin County a couple years ago now. I joined Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers association and attended every seminar I could, driving to Tyler, Corpus Christi, Huntsville for Criminal Trial College and even Laredo for a seminar. I eagerly wanted to learn how to protect my clients and learned the tools of the trade as fast as I could. This also helped me become board certified in the shortest time possible in 2010, with five years experience. I did a lot of administrative license review hearings for DWIs and it was easier to win them back then. There was a form on which I just had to request the arresting officer and breath tech supervisor, the latter who virtually never showed up for hearings because there is only one or two in the region and they handle the trials as well. I was proud to save a lot of drivers licenses. Texas eventually changed the law and we now have to subpoena the arresting officer and have to meet a virtually insurmountable burden to force the breath tech supervisor to appear beyond an affidavit. But, we have been winning close to half of the cases lately.

I joined Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers association and attended every seminar I could, driving to Tyler, Corpus Christi, Huntsville for Criminal Trial College and even Laredo for a seminar. I eagerly wanted to learn how to protect my clients and learned the tools of the trade as fast as I could. This also helped me become board certified in the shortest time possible in 2010, with five years experience. I did a lot of administrative license review hearings for DWIs and it was easier to win them back then. There was a form on which I just had to request the arresting officer and breath tech supervisor, the latter who virtually never showed up for hearings because there is only one or two in the region and they handle the trials as well. I was proud to save a lot of drivers licenses. Texas eventually changed the law and we now have to subpoena the arresting officer and have to meet a virtually insurmountable burden to force the breath tech supervisor to appear beyond an affidavit. But, we have been winning close to half of the cases lately. On November 5, 2025, I will have practiced law for twenty years. I started out in 2005 with a desk, phone and covering the hearings for a personal injury attorney in 2005 in Sherman, TX. The local judges had known me from interning for Sheriff Keith Gary, Judge Paul Brown, and District Attorney Joe Brown, so let me start with state jail felonies and third degree felony appointments rather than just misdemeanors. I mainly covered criminal and family law hearings for him while I built up my own practice through court appointments, referrals and advertising on the internet and otherwise. I even bought matches and coasters with my information and placed them at the local bars and bar/restaurant scene in Grayson and Cooke county. I sent direct mails to DWI arrests in Grayson and Fannin county, encouraging them to come in before their drivers license was automatically suspended if they didn’t request the ALR hearing within 15 days. The only case I know for sure to have come from one of the matchbooks was an important felony aggravated assault case in Cooke County that ended up being my first jury trial win in 2006. My client had chased his ex up and down highway 82 in Gainesville to retrieve his daughter from her vehicle, as it was his day for custody and she was playing games. She happened to be friends with the police officers, who arrested him for aggravated assault when he backed his car into hers in the median. We got a misdemeanor fine only and no jail time from a very fair jury.

On November 5, 2025, I will have practiced law for twenty years. I started out in 2005 with a desk, phone and covering the hearings for a personal injury attorney in 2005 in Sherman, TX. The local judges had known me from interning for Sheriff Keith Gary, Judge Paul Brown, and District Attorney Joe Brown, so let me start with state jail felonies and third degree felony appointments rather than just misdemeanors. I mainly covered criminal and family law hearings for him while I built up my own practice through court appointments, referrals and advertising on the internet and otherwise. I even bought matches and coasters with my information and placed them at the local bars and bar/restaurant scene in Grayson and Cooke county. I sent direct mails to DWI arrests in Grayson and Fannin county, encouraging them to come in before their drivers license was automatically suspended if they didn’t request the ALR hearing within 15 days. The only case I know for sure to have come from one of the matchbooks was an important felony aggravated assault case in Cooke County that ended up being my first jury trial win in 2006. My client had chased his ex up and down highway 82 in Gainesville to retrieve his daughter from her vehicle, as it was his day for custody and she was playing games. She happened to be friends with the police officers, who arrested him for aggravated assault when he backed his car into hers in the median. We got a misdemeanor fine only and no jail time from a very fair jury. Judging delay is one area where analysis under the due diligence doctrine remains relevant. Under the due diligence doctrine, the court looks to whether “reasonable investigative efforts [were] made to apprehend the person sought.” Peacock, 77 S.W.3d at 288. Per Peacock, such a requirement “helps a court determine whether the probationer cannot be found because he is trying to elude capture or because no one is looking for him,” and in the case of the latter “the State should not benefit by doing nothing meaningful to execute a capias.” The Court of Criminal Appeals has made clear that merely sending a letter to the Defendant’s home and uploading a warrant into the TCIC database does not constitute diligence on the part of the State. Peacock, 77 S.W.3d at 288-89. A probation who stays in state at a known address and known phone number, without probation coming to look for him and arrest him, has a great due diligence claim. A Texas resident who stays in the State at a known address and phone number also can show unreasonable delay if a warrant is issued at large for their arrest for a new crime and no effort is made to apprehend them. Leaving the state or country, however, can cause the speedy trial right to be tolled, and doing so is a factor that will hurt the defendant in a speedy trial analysis.

Judging delay is one area where analysis under the due diligence doctrine remains relevant. Under the due diligence doctrine, the court looks to whether “reasonable investigative efforts [were] made to apprehend the person sought.” Peacock, 77 S.W.3d at 288. Per Peacock, such a requirement “helps a court determine whether the probationer cannot be found because he is trying to elude capture or because no one is looking for him,” and in the case of the latter “the State should not benefit by doing nothing meaningful to execute a capias.” The Court of Criminal Appeals has made clear that merely sending a letter to the Defendant’s home and uploading a warrant into the TCIC database does not constitute diligence on the part of the State. Peacock, 77 S.W.3d at 288-89. A probation who stays in state at a known address and known phone number, without probation coming to look for him and arrest him, has a great due diligence claim. A Texas resident who stays in the State at a known address and phone number also can show unreasonable delay if a warrant is issued at large for their arrest for a new crime and no effort is made to apprehend them. Leaving the state or country, however, can cause the speedy trial right to be tolled, and doing so is a factor that will hurt the defendant in a speedy trial analysis. But, despite the elimination of the common law due diligence “scheme,” the Court of Criminal Appeals has recognized in both pre-Garcia case law and post-Garcia case law that there exists a Constitutional speedy revocation hearing right even where claims of common law due diligence do not lie. The Court of Criminal Appeals specifically held this to be the case in Ballard v. State, stating “[a]lthough such a defendant cannot advance a due diligence defense, he has the statutory twenty-day remedy, and in appropriate circumstances, may have a Constitutional speedy hearing claim under Barker v. Wingo.” 126 S.W.3d 919, 921 n.8 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004)(citations omitted). The 20-day remedy is found in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Article 42A.751(d) (If the defendant has not been released on bail as permitted under Subsection (c), on motion by the defendant, the judge who ordered the arrest for the alleged violation of a condition of community supervision shall cause the defendant to be brought before the judge for a hearing on the alleged violation within 20 days of the date the motion is filed.)

But, despite the elimination of the common law due diligence “scheme,” the Court of Criminal Appeals has recognized in both pre-Garcia case law and post-Garcia case law that there exists a Constitutional speedy revocation hearing right even where claims of common law due diligence do not lie. The Court of Criminal Appeals specifically held this to be the case in Ballard v. State, stating “[a]lthough such a defendant cannot advance a due diligence defense, he has the statutory twenty-day remedy, and in appropriate circumstances, may have a Constitutional speedy hearing claim under Barker v. Wingo.” 126 S.W.3d 919, 921 n.8 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004)(citations omitted). The 20-day remedy is found in Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Article 42A.751(d) (If the defendant has not been released on bail as permitted under Subsection (c), on motion by the defendant, the judge who ordered the arrest for the alleged violation of a condition of community supervision shall cause the defendant to be brought before the judge for a hearing on the alleged violation within 20 days of the date the motion is filed.) A Defendant formally accused of violating probation also has the right to a speedy revocation hearing. In addition to statutory provisions addressing timeliness in motions to revoke, the Court of Criminal Appeals has historically recognized two sources of law which provide for the right to a speedy revocation hearing: (1) the statutory and former common law doctrine of due diligence, and (2) Constitutional speedy hearing rights under Barker v. Wingo. 407 U.S. 514 (1971). of due diligence has been superseded by statute in Article 42A.751(d).

A Defendant formally accused of violating probation also has the right to a speedy revocation hearing. In addition to statutory provisions addressing timeliness in motions to revoke, the Court of Criminal Appeals has historically recognized two sources of law which provide for the right to a speedy revocation hearing: (1) the statutory and former common law doctrine of due diligence, and (2) Constitutional speedy hearing rights under Barker v. Wingo. 407 U.S. 514 (1971). of due diligence has been superseded by statute in Article 42A.751(d). The reasons for the delay of a trial are important under the second prong, and the State will be required to put forward their reasons at a dismissal hearing. Right now, blood and drug results from the State laboratory are taking six months or so to process. A person sitting in jail on a misdemeanor is heavily prejudiced by waiting that long on a chemical result. A person awaiting felony trial is not as prejudiced per the caselaw, but after nine months or so prejudice can sometimes be shown. A lawyer should consider filing a speedy trial motion in any trial that will be lengthily delayed by chemical testing, DNA testing or other factors under the State’s control.

The reasons for the delay of a trial are important under the second prong, and the State will be required to put forward their reasons at a dismissal hearing. Right now, blood and drug results from the State laboratory are taking six months or so to process. A person sitting in jail on a misdemeanor is heavily prejudiced by waiting that long on a chemical result. A person awaiting felony trial is not as prejudiced per the caselaw, but after nine months or so prejudice can sometimes be shown. A lawyer should consider filing a speedy trial motion in any trial that will be lengthily delayed by chemical testing, DNA testing or other factors under the State’s control.